The History

From Winegrowers to Engineers

For more than four centuries, the members of the Méo family have devoted themselves to growing vines and making wines. They came originally from the Burgundy village of Selongey, in the north of Côte d’Or, where today, even if the vines, alas, have disappeared, a pressing house, dating from the year 50 AD, bears witness to the presence there of Gallo-Roman winegrowers.

It was thanks to Jean Méo’s mother, Marcelle Lamarche-Confuron, originating from an old winegrowing family in Vosne (with already a small activity as négociants), that the Méos came to settle in Vosne-Romanée.

Jean Méo’s grandmother was the first cousin of Étienne Camuzet (1867-1946), a winegrower in Vosne-Romanée, mayor of the village, and also an MP for Côte d’Or from 1903 to 1932. In 1920, he had the opportunity to purchase the Château du Clos de Vougeot with some of the vines, but instead of living there, he preferred to lodge his tenant farmers in it as he no longer had time to look after his own vineyards. He was to sell it in November 1944 to the Confrérie des Chevaliers du Tastevin.

As for the vines, it was the 20 hectares (50 acres) at the top of the Clos that were for sale…Étienne Camuzet enlisted the help of his fellow winegrowers from Vosne-Romanée to acquire them. He would keep 3 hectares (7.5 acres) himself, immediately below the château.

Following the death of Étienne Camuzet, his daughter, Maria Noirot, inherited the estate and retained the tenant farmers. She had no children, however, and when she died, in 1959, she bequeathed the estate to her nephew, Jean Méo, who at that time had already left Vosne-Romanée, and since 1958 had been a member of General de Gaulle’s cabinet. Having been regularly in close contact with his uncle, who had shared with him his passion for the vine, teaching him to respect and love wine, the youngest of the Méos could not allow the winegrowing saga of the family to come to an end. He decided, therefore, to take the estate in hand, with help from his father, Gaston, initially, and then from his mother. In that way, Jean Méo was able to remain with General de Gaulle and to pursue his career in Paris, which would lead him to manage in succession several large companies: ELF, France Soir, Agence Havas, Institut Français du Pétrole, and others. He was also elected to the European Parliament and sat on the Council of Paris. Throughout that period, he relied on four tenant farmers, including the great winegrower, Henri Jayer, who was one of the first to control temperatures systematically during vinification, always bringing out the freshness and the fruit, thus making the nose and the texture of the wine more attractive. Jean Méo was to manage the estate from 1959 to1984, after which he called upon the new generation.

In 1981, the Camuzet estate became Méo-Camuzet, and the first wines bottled under that name were those of the 1983 vintage.

The New Generation

In 1984, Jean Méo proposed that his son should take over the reins of the estate. Just 20 years old and a student at ESCP (the Paris business school), Jean-Nicolas had had no preparation to become a winegrower, but he soon began to immerse himself in the estate, the vineyards, and the winemaking with his father as his mentor, but also Henri Jayer, who was taking retirement but agreed, nonetheless, to share with him his technical know-how and his art of winemaking. Christian Faurois, son and nephew of other historic tenant farmers, taught him about growing vines and passed on to him his passion for the vineyard.

At this time, the sale of wine in bottles with the Méo-Camuzet estate label had already begun (with the 1983 vintage). This was the decision of Jean Méo, who had immediately aimed at a high level of exports, particularly to the USA. Previously, the wines had been sold to négociants in Beaune or Nuits and the few bottles kept for the family carried the Camuzet or Veuve Noirot-Camuzet label marked “Jean Méo, propriétaire à Vosne-Romanée.”

By 2008, the tenant farmers had all taken retirement and Jean-Nicolas now farmed all of the estate’s vineyards. His main difficulty was managing the insufficient supply in a context of increasing demand. At the turn of the century, therefore, he decided, in collaboration with his sisters, to set up a new company: as négociants, they could meet that demand a little better and widen the range in order to take in more affordable wines.

Thus was born the Méo-Camuzet Frère & Soeurs company, with its own specific label. Jean-Nicolas’ conception of négoce, though, is not the traditional one. Indeed, he buys harvests, on the vine, in Fixin, Marsannay, Bourgogne, or other vineyards, but that doesn’t mean just buying grapes. Several interventions are carried out during the growing season by the estate’s teams, and most of these plots are monitored for several years, which make it possible to get to know them as well as the grower does. In fact, it’s very much like renting land.

Today, the Méo-Camuzet is among the most renowned estates in Burgundy. Jean-Nicolas and his team continue to work on the nose and the taste of their wines, showing respect for nature and passion for the terroir and their profession.

The Approach

The objective of the estate is to produce wines that combine structure and finesse, concentration and charm. This balance must be achieved, while respecting the personality of the terroir and the vintage. To do this, it’s necessary to show a great deal of respect at each stage of the wine-making process. And that must start in the vineyard!

Various procedures are implemented to realize these objectives: the viticulture seeks to favor the natural balances and reveal the terroir; yields are kept under control, harvesting is carried out carefully by hand, and grapes are sorted prior to the winemaking procedure characterized by minimum interference. This encourages the fineness, the expression of the fruit, and the personality of each wine rather than just extraction. Maturing is carried out carefully, with the extensive but controlled use of new casks. The wines are bottled without being fined or filtered.

Work in the Vineyard

The pruning must meet numerous objectives: to produce grapes, but also to ensure the plant’s equilibrium and, if possible, to avoid diseases, particularly those affecting the wood, that have multiplied in recent years.

In order to ensure that the leaves absorb enough light and that the bunches have enough air, one has to prune long; but obviously, to avoid the vines being subsequently overloaded, it will be necessary in May to eliminate some buds or branches on the canes thus pruned.

To keep the sap-flow within the plant well balanced, one must make sure that “eyes” are maintained on both sides of the row, as these will ensure the renewal of the producing branches. During the vegetative cycle, the winegrowers go through the vines (up to 4 times), row by row, separating the branches to keep them from becoming entwined: the vine is a creeper and it clings to whatever it can find. Along the same lines, the height of the foliage is raised and the leaves at the bottom are eliminated which leads to better aeration of the area where the grapes grow as well as increased ripeness.

Organic viticulture requires increased attention; to keep the weeds under control is tedious work: no herbicide is used, making it necessary to plough five times a year. In fact, the horse is being reintroduced in difficult places.

The Grape Harvest

The month leading up to the grape harvest is a worrying time for the winegrower: his capacity to react is limited, given that the slightest climatic variation will have its consequences on the quality of the vintage. The date of the harvest obeys several constraints: to have the ripest and healthiest fruit possible, to take advantage of the best possible weather, and to manage the harvest team in the best possible way.

The object is to obtain grapes of maximum ripeness which, for Pinot Noir in Burgundy, is situated somewhere around 13% ABV. At this level, one generally obtains a good concentration of sugar, which produces voluptuous wines with enough acidity to preserve the freshness.

The harvest is done manually, for the simple reason that it’s not possible to sort a harvest done by machine, and unless the vintage is homogeneous (which is rarely the case) that can prove disastrous.

The grapes are then sorted on a table in the winery before being put into the vat. In the winery, there’s a team of 6 to 12 people at the sorting table, usually supervised by JNM, who remove the damaged or insufficiently ripe grapes. The proportion thus eliminated varies between 5-20% according to the vintage and the appellation.

When bringing the grapes into the winery, crates are used which contain between 15 and 20 kg of harvest to avoid too much pressure being exerted on the grapes. They must be transported gently: the crates are loaded onto a tipper truck, which will shake the grapes much less than a trailer hooked up to a tractor. These trays have holes in them: the juice which escapes due to the weight of the harvest, which nonetheless is kept to a minimum, is thus eliminated, which is a good thing, as it has had time to oxidize during transport.

Vinification

The grapes are left to macerate at a low temperature (about 15°C or 60°F) for 3 to 5 days before the juice begins to ferment naturally. During the fermentation, temperatures are controlled (but not directed), so that they do not go above the critical threshold of 34-35°C (around 95°F), beyond which the activity of the yeasts might slow down or even stop.

At the beginning, a method called pumping over is employed, in other words pumping the juice from the bottom of the vat so as to spray the grapes which are at the top. Then towards the end of the fermentation, pigeages are carried out, which means forcing the berries (the “cap”) down into the fermenting juice. This presses them slightly and liberates the seeds and thus the tannins.

It’s better if this fermentation cycle, which lasts from two to three weeks, comes to an end gradually, and the concrete vats, which guarantee more reliable sterilization from one harvest to the next than wooden vats, help to maintain warmer temperatures that decrease slowly.

Not much extracting is done, nor is the harvest processed or pushed around too much: very little sulfur, very little chaptalization or acidification, with pigeages only at the end of the fermentation.

Maturation

Whether to use new oak casks or not is an important decision: a cask enables a wine to oxidize gently through the pores of the wood, which stabilizes it, but also brings aromas that blend together with those of the wine, or become dominant. A cask that has already been used leaves less of a “mark” on the wine, but after a few years, loses its powers of aeration, as the pores and the chinks between the pieces of wood gradually become blocked.

If one decides to put a wine in new casks, the toasting, the type of oak (origin, technical characteristics) must be adapted to the appellation, not to mention the proportion used. Adapting the proportion of new casks to the vintage is not reliable; the character of each wine as it emerges over the years is a far better indicator.

Other circumstances are also very important: when and how quickly the malolactic fermentation (not induced) takes place, the interaction with the lees, managing the rackings and the degree of aeration you want your wines to have…each stage must be carefully thought out.

Bottling

The wines are racked, the different casks of the same appellation are brought together in a tank 3 to 4 weeks beforehand and the bottling takes place after a maturing period in casks of 17 months on average (the wines of year 1 are bottled between January and July of year 3).

During this period, they are tasted several times in order to judge their readiness: we know them, we know what they are capable of achieving and can judge whether they need extra aeration, more time, etc… Some technical parameters (temperature, levels of CO2, SO2, etc.) are also monitored.

Generally speaking, the period for bottling is determined in advance according to the lunar calendar, but one must be able to adapt to the weather (never bottle during a depression), to the availability of manpower, etc.

The wines are bottled by gravity without any filtration, a longer (the clarification takes place naturally and over time) but much more respectful process. With the occasional exception (particularly for the whites), there is no fining, as the wines don’t need it for their stability. In this way, they suffer no trauma. Always the same general principal at the estate: respect the raw material, treat the wine for what it is, a living substance which demands consideration.

A modern bottling chain enables the winemakers to take all the necessary precautions in order to ensure high-quality corking and thus the good aging of the wines: washing and inerting the bottles, a vacuum between the wine and the cork to avoid high pressure, equal levels of wine. The corks are carefully selected and strict specifications are imposed on our suppliers.

After the bottling, the vine-grower’s work is finished, so to speak: it’s then up to the wine-lover to ensure optimum storage (15°C or 60°F) maximum) and drinking conditions.

Corton Grand Cru Les Perrières

The Vines: 100% Pinot Noir; The age of the vines is beginning to be venerable (planted in the 1950’s) and most certainly influences the character of the resulting wine. The grapes are rather small and frequently suffer from millerandage, or uneven ripening and or sizes within a grape bunch. The grapes tend to ripen early, so it is important not to harvest too late in the season.

Location: Located south of Nuits-St-Georges, this premier cru is quite high up on the hill where the soil is stony with average depth.

The Soil: A fine plot of about one and a half acres, situated just north of the village of Aloxe. “Perrières” refers to “stones” because the soil contains numerous round stones, often pink in color. The soil is quite deep, but always full of stones. The orientation is typical of red Cortons, facing due east, and the plot lies more on the lower part of the slope.

Vinification: Naturally fairly slow, it requires very little intervention as the beautiful complexity emerges on its own.

Maturation: The wine stands up well to new casks, particularly of Tronçais oak. However, its delicate character and its propensity to evolve quite quickly at the beginning, make us cautious concerning not only the proportion of new oak, but also the way we handle this wine when racking or bottling it.

Cellaring Potential: Very pleasant at the beginning, it will teach you a lot about the vintage, if you want to try a wine without opening a bottle which you know will be far from ready for drinking. Nevertheless, it’s a wine which keeps very well and ages most harmoniously.

Echezeaux Grand Cru Les Rouges du Bas

The Vines: The original planting dates from the end of the 40s, but about one quarter of this was renewed a few years ago. The grapes are small, particularly at the top. They ripen quickly, and a high sugar level combined with excellent acidity can often be observed, and this produces wines of intensity. The only difficulty is that these are grapes which have to be ‘snapped up’ at harvest time: you cannot wait, or they will spoil.

Location: As its name – ‘les Rouges du Bas’ – does not indicate, this vineyard plot of about 1 acre, is situated at the upper limit of the Échezeaux appellation. The altitude explains perhaps the aromatic freshness often found in this wine, even though its east/south-east orientation also influences its early maturity. The nature of the soil changes with the altitude: lighter and lighter as you get higher.

Vinification: The vinification requires little intervention, as the grapes already contain the elements which it takes to succeed.

Maturation: Its development is slow, and right up to the moment when it is bottled, the wine is a little austere. Time is necessary, for this is a wine which tends to remain indifferent to whatever treatments you try to apply to it. It must like to be left alone. It may just react to new casks, Bertranges being the oak that is the most successful.

Cellaring Potential: This wine needs to be kept for a long time if it is to reveal all its richness. The natural acidity contained in the grapes tends to constrict it somewhat when it is young, and time must play its part to make it better balanced.

Santenay Cuvée Christine Friedberg Hospices de Beaune

History: In April 2010, William D. Friedberg donated to the Hospices de Beaune a parcel of the appellation d’origine Santenay, with a surface area of 0.6 hectare and planted with Pinot Noir grapes.

William D. Friedberg was, until recently, a wine importer in Boston, Massachusetts. He is a lover of the Burgundy region and of the wine auction of the Hospices de Beaune, at which he has been present for over 20 years, regularly participating in the bidding.

Through his generous gesture, he wishes to honor the memory of his dearly departed wife, Christine, who was also a great lover of Burgundy. The production of this parcel of Santenay, which is cultivated to enrich the viticultural heritage of the Hospices, will bear the name of “Cuvée Christine Friedberg.”

Soil: Clay & limestone

The Vines: 0.6 ha of Les Hates

Grape Varietals: 100% Pinot Noir

Tasting Notes: Good structure with a lovely freshness, and a slight dryness on the palate.

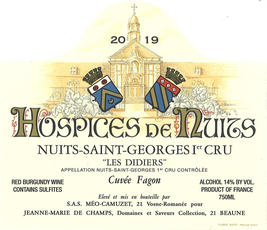

Nuits-Saint-Georges 1er Cru Hospices De Nuits Les Didiers Cuvée Fagon

The History: The origins of the Hospices de Nuit date back as early as 1270, but it was in 1692 when King Louis XIV united the many small “maladières” of Nuits into one larger hospital. In contrast to their cousin, Hospices de Beaune, the architecture of Hospices de Nuit has not made as big of a cultural impact, not has it maintained any significant archives, despite having a long and rich history of lands and vineyards being donated to the domaine.

In the past, the Hospices de Nuits sold their wine in bulk to the négoce, but all that changed in 1961 when, like Hospices de Beaune, they began their own auction. This is the ideal setup for a charity like the Hospices de Nuits as there is no need for a commercial department, there are no importers to deal with, few visitors, and the actual bottling of the wine is the responsibility of someone else.

The Vines & Vinification: Jean-Marc Moron manages the viticulture and the vinification of the Hospices de Nuits. A large seasonal team of pickers are used for the harvest, with a staff of 4 full-time employees for the rest of the year to care for the domaine’s 12.5 hectares and to manage wine production. The vines are situated within the districts of Nuits St. Georges (including Premeaux), Vosne-Romanée, and Gevrey-Chambertin. Jean-Marc Moron describes his winemaking methods as being ‘très raisonnée’ but also pragmatic; because he is responsible for delivering the income of the domaine to a charity, he does not have the luxury of being able to employ Biodynamic methods. However, he makes a point of using as few treatments on the vines as possible.

The domaine typically yields 30-35 hl/ha annually; there is a single application of herbicide out of the growing season, and then the dead material is plowed into the soil, with the additional use of pheromones throughout the growing season.

Grapes are harvested manually then triaged back at the winery. Grapes are destemmed before fermenting in stainless-steel tanks; the tanks may be cooled to 14°C if the temperature is higher, after which fermentation is allowed to take its normal course. Cooling of the tanks is possible and a system of automatic punching-down (pigeage) is employed. The wine is then fed by gravity into 100% new oak from a mix of 3 barrel-makers: Damy, Berthomieux and Sirugue. All barrels have the equivalent toasting of ‘moyen-fort’ or medium-strong. The barrels rest in an underground cellar directly beneath the winery.

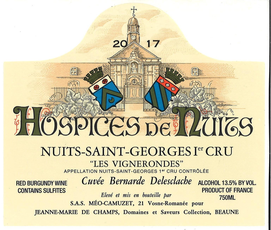

Nuits-Saint-Georges 1er Cru Hospices De Nuits Les Vignerondes Cuvée Bernarde Delesclache

Region: Côte de Nuits

Village: Nuits-Saint-Georges

Level: Premier Cru

AOC: Nuits-Saint-Georges 1er Cru

Grape variety: 100% Pinot Noir

Terroir: Les Vignerondes

Tasting: This cuvée from Les Vignesrondes (round vineyards in French) displays an intense red colour. Fruit intensity with a majority of black berries and currants. With a few years, this fine wine will evolve towards wild cherries and hints of liquorice and fresh leather.

Food Pairings: Slow-cooked lamb shank, Burgundy-style beef stew to stay local!